In 1830, a rapidly growing settlement on the banks of the Mississippi River shipped more cotton than any other port in the region and was described as "the great steamboat depot of West Tennessee." It wasn't Memphis.

Like planets, cities have a gravitational pull. As a city grows, its gravity becomes stronger and it attracts people and economic activity. The more it attracts, the larger it grows. The larger it grows, the more it attracts.

A metropolitan statistical area (MSA) is the region that has fallen under the gravitational influence of the core city. The Memphis MSA spans nine counties in Tennessee, Arkansas, and Mississippi; these counties contain dozens of small, independent towns and municipalities, but their futures and fortunes are inextricably tied to Memphis.

After a city achieves a certain mass, it seems inevitable that it will become the core of an MSA. But before then, that role is up for grabs. Was it inevitable that, of all the settlements in the area, Memphis would be the one to achieve critical mass? Why is a town like Randolph, Tennessee, in the Memphis metropolitan area, rather than Memphis being in the Randolph metropolitan area? The answer is not so obvious.

A good place to start is geography. Did geography alone make Memphis the best candidate to become the dominant commercial center in the region? No. Imagine it's 1830, and you're given the task of choosing where in the Mid-South to place a city. Before the urban geography was settled, the dominant industry was agriculture, so the most promising location would be one with favorable conditions for trading, warehousing, and shipping agricultural commodities. You would eliminate the cities without access to the Mississippi River. The river is/was prone to changing courses, so of the cities on the Mississippi, you would eliminate the ones not located on a deepwater channel where the river's course is fixed. Finally, the river is extremely prone to flooding, which makes storing commodities risky, so you eliminate the cities not on high ground. Memphis, high above a deepwater channel in the Mississippi on the Fourth Chickasaw Bluff, is still in the running. But Memphis is not unique in its geographic advantages.

You might consider planting your city near Randolph, Tennessee. Similar to Memphis, Randolph has a flood-safe location on the Second Chickasaw Bluff above the Mississippi River. The river runs deep at Randolph, which made it unlikely to change course. Randolph even had a slight edge: the city sat at the confluence of the Mississippi and a tributary, the Hatchie, navigable 70 miles inland. Memphis' tributary, the Wolf, was only navigable 10 miles inland.

An observer in 1830 might bet on Randolph. Not only did the city have similar, perhaps better, geographical advantages, but Memphis was crippled by repeated disease outbreaks. In 1830, Memphis had a population of 663. Randolph had a population of about 1,000. Randolph was a more important shipping center than Memphis and shipped more cotton.

But we know how this story ends. So what saved Memphis?

The Post Office. In 1829, near the peak of Randolph's commercial success, the postal service delivered a crippling blow to the fledgling regional capital: the main postal route was placed through Memphis, the sickly city to the South, rather than Randolph. The route connected Memphis and Nashville and brought mail thrice weekly. Randolph, with its once weekly delivery, instantly became more remote than Memphis. Mail, the only facilitator of long distance communication and economic transactions, was the lifeblood of the early 1800s economy, and the improvement in infrastructure that accompanied the development of the postal route drove people and activity through the city. Railroads soon followed. Memphis' gravity grew stronger, and was soon strong enough to attract economic activity away from Randolph. Randolph fell into Memphis' sphere.

This narrative glosses over a few facts about Randolph's decline. Shortly after the town was founded in 1823, a faulty land title cast doubt over the ownership of the land the town was built on. The promise of a canal connecting the Tennessee and Hatchie rivers never materialized. Attempts to attract a railroad failed. And to put the final nail in Randolph's coffin, federal troops burned the town during the Civil War. Twice.

The land title and the burning of the town were exogenous events that severly damaged Randolph's prospects. But other frequently cited factors in Randolph's decline occurred after the establishment of the postal route and may be symptoms rather than additional causes.

In the first decades of the 19th centuy, the region's burgeoning agricultural economy needed a commercial center, and two cities were at the tipping point. The postal route pushed Memphis to critical mass. Gravity did the rest.

Friday, September 13, 2013

Thursday, September 5, 2013

Solow Act

Is Memphis on a long term path to prosperity?

As of the last Census, Memphis was the poorest large metropolitan area in the county. With Memphis' level of poverty, it will take more than a rising economic tide to lift the fortunes of the Bluff City; we need economic global warming with a subsequent rise in sea levels fueled by melting economic glaciers.

Tides are cyclical, but melting glaciers are a long run trend. And despite not experiencing the uptempo growth of similar sized cities like Austin and Nashville (maybe Memphis put its eggs in the wrong musical basket), Memphis' long run trend is lumpy but positive. But can we say anything more optimistic?

One theory of economic growth provides a glimmer of hope. Like other models of economic growth, such as the Malthusian model, the Solow growth model relies on a production function and a tendency towards a steady state point. A diagram of the Solow model is identical to a diagram of the Malthusian model, but with different axes: rather than labor on the horizontal axis and output/income on the vertical axis, the Solow model has capital per worker on the horizontal axis and savings/investment per worker on the vertical axis. And instead of a subsistence line, we have a balanced growth investment per worker line. Production remains a function of labor, capital, and technology, and still has diminishing marginal returns. (A few adjustments are needed to express the production function in per worker terms and to derive a savings/investment function from the production function, but the analysis remains essentially unchanged).

In this model, capital is key. The growth of the economy is determined by the growth of capital. At the steady state point, capital per worker is constant at the "balanced" level. At this level, the growth of capital is keeping up with depreciation and the growth in population. If we are to the left of the steady state point, the growth of capital is outpacing depreciation and the growth in population; therefore, capital per worker must be increasing (capital deepening). Capital is an input to production, so production per worker is increasing, and therefore saving is also increasing. So, we move along the savings function to the right. If we are to the right of the steady state point, the growth of capital is not keeping pace with depreciation and the growth in population, so capital per worker must be decreasing. Output per worker is decreasing, so saving is also decreasing, and we move along the savings function to the left. The economy tends towards the steady state, where saving is just enough to keep capital per worker constant.

What does this mean for Memphis? Among economies with the same production functions and the same access to technology, the model predicts convergence: poor economies should grow more quickly and catch up to wealthy economies. Workers in poor economies have less income and save less; because saving determines the growth of capital, capital per worker is lower. But because of diminishing marginal returns, the rate of return on capital is higher for the poor economy. Although workers in the poor economy save less, the higher return on capital means production/income per worker is growing faster. Faster growth in income means faster growth in saving, which means faster growth in capital per worker. Capital per worker will increase in the poor economy relative to the rich economy, until they are both at the same steady state point with the same income per capita.

It's reasonable to argue that cities in the United States have the same production function and access to technology, so we should expect convergence. If convergence were occurring, the cities (metropolitan statistical areas, or MSAs) with the highest income initially would grow more slowly than the cities with the lowest income initially. Lo, and behold! This is the case:

As of the last Census, Memphis was the poorest large metropolitan area in the county. With Memphis' level of poverty, it will take more than a rising economic tide to lift the fortunes of the Bluff City; we need economic global warming with a subsequent rise in sea levels fueled by melting economic glaciers.

Tides are cyclical, but melting glaciers are a long run trend. And despite not experiencing the uptempo growth of similar sized cities like Austin and Nashville (maybe Memphis put its eggs in the wrong musical basket), Memphis' long run trend is lumpy but positive. But can we say anything more optimistic?

One theory of economic growth provides a glimmer of hope. Like other models of economic growth, such as the Malthusian model, the Solow growth model relies on a production function and a tendency towards a steady state point. A diagram of the Solow model is identical to a diagram of the Malthusian model, but with different axes: rather than labor on the horizontal axis and output/income on the vertical axis, the Solow model has capital per worker on the horizontal axis and savings/investment per worker on the vertical axis. And instead of a subsistence line, we have a balanced growth investment per worker line. Production remains a function of labor, capital, and technology, and still has diminishing marginal returns. (A few adjustments are needed to express the production function in per worker terms and to derive a savings/investment function from the production function, but the analysis remains essentially unchanged).

In this model, capital is key. The growth of the economy is determined by the growth of capital. At the steady state point, capital per worker is constant at the "balanced" level. At this level, the growth of capital is keeping up with depreciation and the growth in population. If we are to the left of the steady state point, the growth of capital is outpacing depreciation and the growth in population; therefore, capital per worker must be increasing (capital deepening). Capital is an input to production, so production per worker is increasing, and therefore saving is also increasing. So, we move along the savings function to the right. If we are to the right of the steady state point, the growth of capital is not keeping pace with depreciation and the growth in population, so capital per worker must be decreasing. Output per worker is decreasing, so saving is also decreasing, and we move along the savings function to the left. The economy tends towards the steady state, where saving is just enough to keep capital per worker constant.

It's reasonable to argue that cities in the United States have the same production function and access to technology, so we should expect convergence. If convergence were occurring, the cities (metropolitan statistical areas, or MSAs) with the highest income initially would grow more slowly than the cities with the lowest income initially. Lo, and behold! This is the case:

In fact, Memphis has outperformed the trend since 1969, growing slightly more quickly than its initial income would suggest.

The business cycle tides have not been favorable to Memphis, but if we bide our time, we may yet float to the top.

Monday, August 26, 2013

In a Jam

A traffic paradox: building more roads doesn't reduce congestion.

In Memphis, the road to riches is constanly under construction. Recently completed or ongoing projects include a multi-year, $4.5 million widening of Poplar in Germantown, a $3.9 million widening of Germantown Road, and a much anticipated segment of Wolf River Boulevard between Farmington and Kimbrough. Will these roads lead Memphis to a headache-free rush hour? Maybe not. A simple economic model leads to a surprising conclusion: building new capacity may not reduce congestion at all.

The key to the paradox lies in the idea of latent demand: Memphians try to avoid roads that will be congested. If congestion is severe enough, many commuters will switch to a different route or even resort to carpooling. So for every vehicle on a congested road, there are other vehicles that would like to use the road but have avoided it. When congestion is reduced by increased capacity, many commuters switch back to the formerly congested road, offsetting the reduction in congestion. In other words, capacity generates its own demand rather than just increasing space for the current drivers on the road.

Another force driving the paradox is the self-interest of drivers. There is a certainly a personal cost to driving on Germantown Parkway during rush hour: you sit bored in traffic listening to the same three songs on the radio and lose time. But there is also a social cost: you add one more vehicle to the congestion, and cause other drivers to sit bored in traffic listening to the same three songs on the radio and lose time. Drivers base their decisions on their personal cost while ignoring the social cost.

The combination of these two forces results in the Pigou-Knight-Downs Paradox (side note: a more apt model for the Wolf River connection is Braess' Paradox).

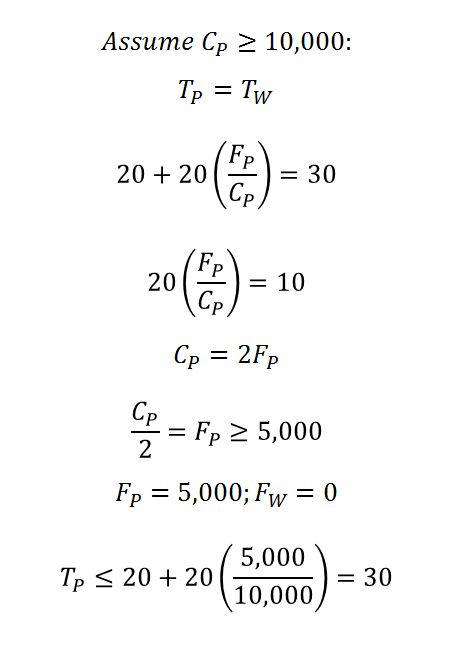

If the capacity of Poplar, C_P, is at least 10,000, twice the total number of drivers in our model (5,000), then there is no paradox. Poplar is always the quickest route, and no one will take Wolf River. But Poplar doesn't have this capacity. Suppose Poplar's capacity is less than 10,000. Then the drivers will choose the quickest route, which will change depending on the number of drivers that choose each route. The result will be that both routes will always take 30 minutes. Wolf River takes 30 minutes regardless of traffic, so if Poplar will take more than 30 minutes, commuters will switch to Wolf River until traffic on Poplar has fallen to the point where both routes take 30 minutes. If Poplar will take 25 minutes, drivers will switch from Wolf River to Poplar until both routes take 30 minutes.

Given that drivers will change their behavior to equalize the travel time on the two routes, what happens when we widen Poplar? Assume that Poplar currently has just enough capacity to carry all 5,000 commuters, but traffic will be tight. If all 5,000 take Poplar, the drive will take 40 minutes. But if drivers choose the shortest route, 2,500 will take Poplar and 2,500 Wolf River. Both routes will take 30 minutes. Suppose a widening project increases the capacity of Poplar to 7,000. Here's the paradox: Poplar will still take 30 minutes! If drivers choose the quickest route, 3,500 will take Poplar and 1,500 will take Wolf River. Capacity generates demand. Only if Poplar's capacity is more than doubled to over 10,000 will travel time on Poplar decrease.

Can increases in capacity reduce congestion? When drivers minimize only private cost (their own driving time), capacity does not reduce congestion. If by law or agreement, the drivers acted to minimize total social cost (the sum of the time it takes everyone to get to their destination), extra capacity does reduce congestion.

Our model suggests that there are more efficient ways to deal with congestion, such as congestion pricing that forces drivers to pay for the negative externalities they generate.

Is road work wasting taxpayer dollars? Our model has some problems: the two routes don't lead to exactly the same place, for instance, and travel time on Wolf River wouldn't remain constant at all levels of traffic. Therefore, it's best to take these results with a grain of salt. But regardless of any model predictions, the distance from Cameron Brown Park to Taco Bell will be cut roughly in half. So I say it's money well spent.

In Memphis, the road to riches is constanly under construction. Recently completed or ongoing projects include a multi-year, $4.5 million widening of Poplar in Germantown, a $3.9 million widening of Germantown Road, and a much anticipated segment of Wolf River Boulevard between Farmington and Kimbrough. Will these roads lead Memphis to a headache-free rush hour? Maybe not. A simple economic model leads to a surprising conclusion: building new capacity may not reduce congestion at all.

The key to the paradox lies in the idea of latent demand: Memphians try to avoid roads that will be congested. If congestion is severe enough, many commuters will switch to a different route or even resort to carpooling. So for every vehicle on a congested road, there are other vehicles that would like to use the road but have avoided it. When congestion is reduced by increased capacity, many commuters switch back to the formerly congested road, offsetting the reduction in congestion. In other words, capacity generates its own demand rather than just increasing space for the current drivers on the road.

Another force driving the paradox is the self-interest of drivers. There is a certainly a personal cost to driving on Germantown Parkway during rush hour: you sit bored in traffic listening to the same three songs on the radio and lose time. But there is also a social cost: you add one more vehicle to the congestion, and cause other drivers to sit bored in traffic listening to the same three songs on the radio and lose time. Drivers base their decisions on their personal cost while ignoring the social cost.

The combination of these two forces results in the Pigou-Knight-Downs Paradox (side note: a more apt model for the Wolf River connection is Braess' Paradox).

To illustrate the paradox, let's simplify the city. Imagine 5,000 workers in Memphis have only two routes home to Germantown or Collierville: Poplar, or Walnut Grove and Wolf River. Assume Poplar is the more direct route, but is narrower and more congested than the less direct but wider Wolf River route. Suppose Poplar takes 20 minutes when there's no traffic but the time it takes rises linearly with the level of congestion (the ratio of the flow of traffic to capacity). Suppose Walnut Grove and Wolf River takes 30 minutes, regardless of traffic. Some notation: define full capacity as the flow of traffic at which the speed falls to half the speed with no traffic. Call the traffic flow on Poplar F_P and the traffic flow on the Wolf River route F_W. Call the capacity of Poplar C_P. Finally, let the time it takes to travel home on Poplar be T_P and the time it takes to travel home on Wolf River T_W.

If the capacity of Poplar, C_P, is at least 10,000, twice the total number of drivers in our model (5,000), then there is no paradox. Poplar is always the quickest route, and no one will take Wolf River. But Poplar doesn't have this capacity. Suppose Poplar's capacity is less than 10,000. Then the drivers will choose the quickest route, which will change depending on the number of drivers that choose each route. The result will be that both routes will always take 30 minutes. Wolf River takes 30 minutes regardless of traffic, so if Poplar will take more than 30 minutes, commuters will switch to Wolf River until traffic on Poplar has fallen to the point where both routes take 30 minutes. If Poplar will take 25 minutes, drivers will switch from Wolf River to Poplar until both routes take 30 minutes.

Given that drivers will change their behavior to equalize the travel time on the two routes, what happens when we widen Poplar? Assume that Poplar currently has just enough capacity to carry all 5,000 commuters, but traffic will be tight. If all 5,000 take Poplar, the drive will take 40 minutes. But if drivers choose the shortest route, 2,500 will take Poplar and 2,500 Wolf River. Both routes will take 30 minutes. Suppose a widening project increases the capacity of Poplar to 7,000. Here's the paradox: Poplar will still take 30 minutes! If drivers choose the quickest route, 3,500 will take Poplar and 1,500 will take Wolf River. Capacity generates demand. Only if Poplar's capacity is more than doubled to over 10,000 will travel time on Poplar decrease.

Can increases in capacity reduce congestion? When drivers minimize only private cost (their own driving time), capacity does not reduce congestion. If by law or agreement, the drivers acted to minimize total social cost (the sum of the time it takes everyone to get to their destination), extra capacity does reduce congestion.

Our model suggests that there are more efficient ways to deal with congestion, such as congestion pricing that forces drivers to pay for the negative externalities they generate.

Is road work wasting taxpayer dollars? Our model has some problems: the two routes don't lead to exactly the same place, for instance, and travel time on Wolf River wouldn't remain constant at all levels of traffic. Therefore, it's best to take these results with a grain of salt. But regardless of any model predictions, the distance from Cameron Brown Park to Taco Bell will be cut roughly in half. So I say it's money well spent.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)